When Humans consume brands, they are really consuming meaning.

That’s why great brand builders are meaning-makers.

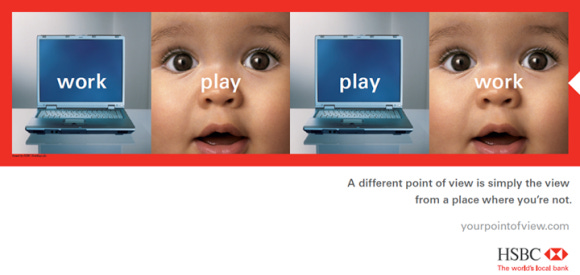

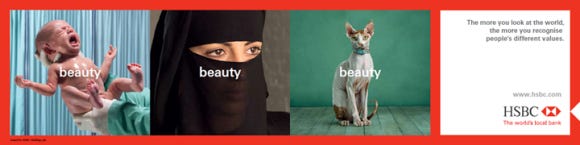

Meaning-makers know what we see and what it means to us don’t always accurately mirror each other.

Sometimes, the same thing has different meanings.

And sometimes, different things mean the same.

One of the tools they use to architect meaning is, you guessed it, Maslow’s hierarchy.

I usually shy away from making black-or-white declarations because context shapes everything. But we must accept that whichever altitude we look from, 30,000 feet or 1 inch, the average consumer in the East is different from his Western counterpart.

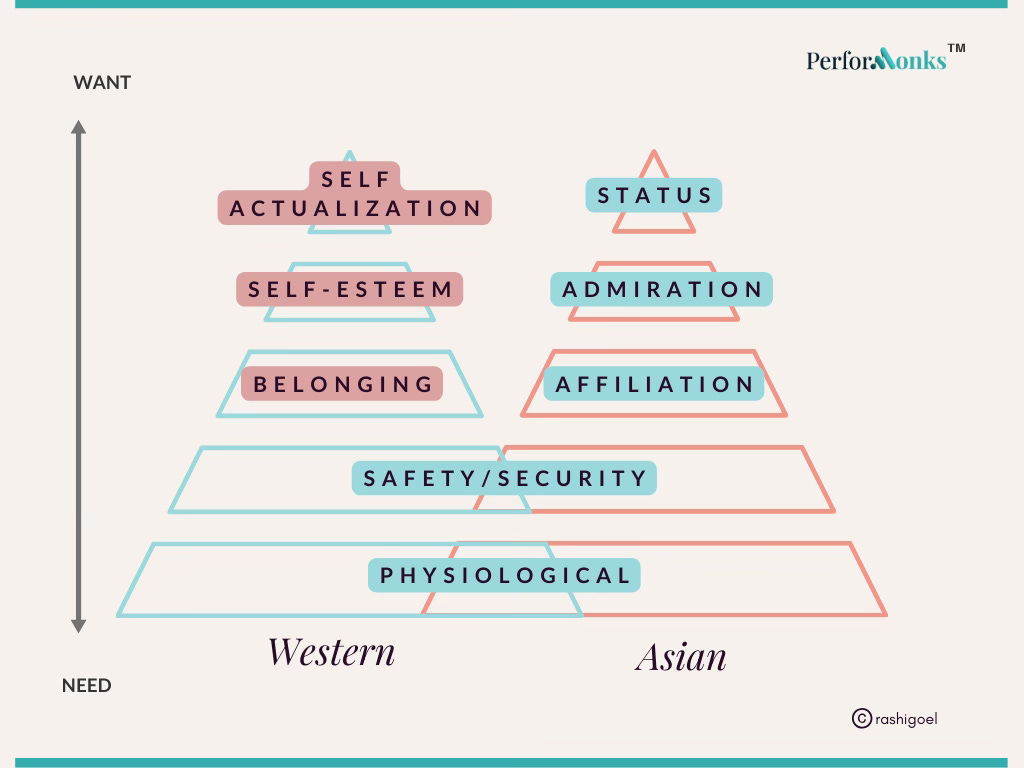

That’s why there are two versions of Maslow.

The leaders in the Hindustan Lever skincare team taught me this in 2001. I now share it with you, with my thoughts.

- Eastern Maslow vs. Western Maslow

- Will I still belong? —>Belonging vs. Affiliation.

- What will people think of me? —>Self-esteem vs. Admiration.

- Will this signal that I am different but the same as everyone?? —> Self Actualization vs. Status.

- Marketing Implications

- Saving Face

- It’s not just that their sense of self is tightly woven with the group; it pays well, too.

- Luxury goods signal that they have made it in life.

1. Eastern Maslow vs. the Western Maslow

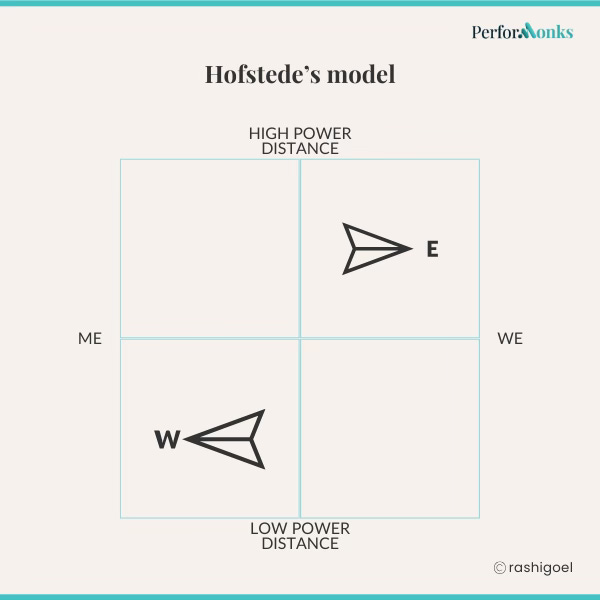

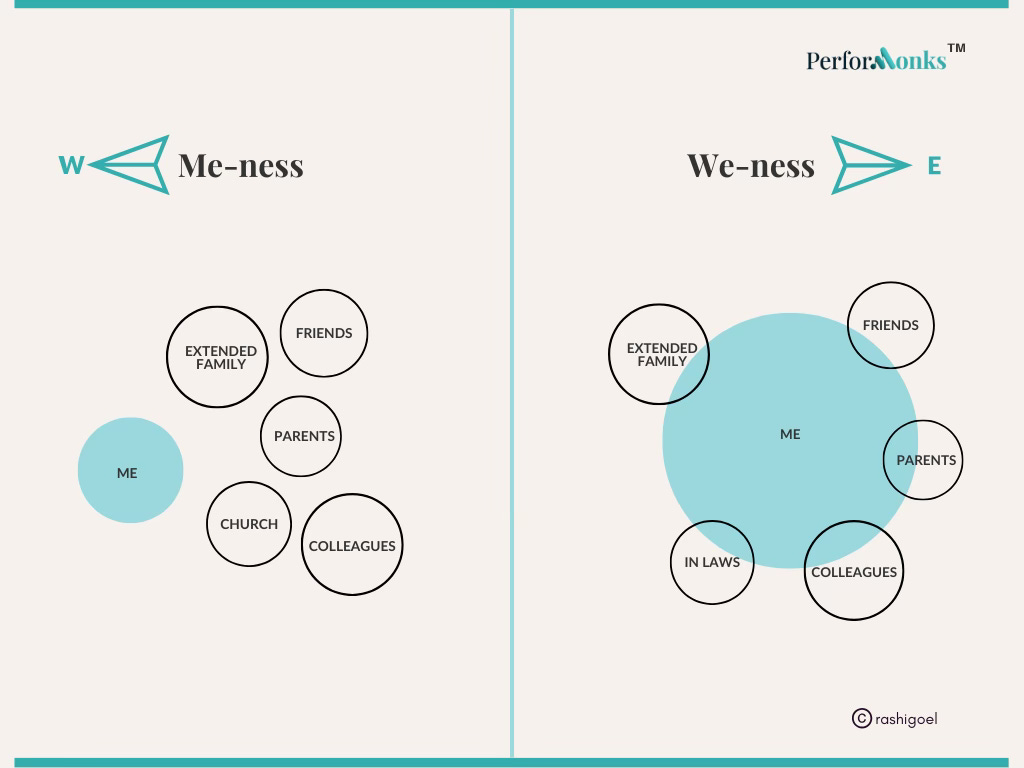

Hofstede’s model explains these cultural differences through six factors. While it’s worth studying all six, Individualism (Me) vs. Collectivism (We) and Power distance explain these differences.

Asian societies value the collective over the Individual. They also value hierarchy (people in power are to be obeyed). This gives us multi-generational families that live together, arranged marriages, a ‘sir-culture,’ and communal eating – Langar, Iftaar, and Hot Pot.

As we move West, the individual is valued more than the collective, and power distance reduces. We find more nuclear families, CEOs addressed by their first names, kids are encouraged to become independent as soon as possible, and single-slice pizza boxes.

This “we-ness” lens changes how Asians make decisions—one, the scale tips in favour of their social ecosystem, and two, they calculate what signals they send to society about themselves.

Therefore, they run their decisions through three filters –

- Will I still belong? —>Belonging vs. Affiliation.

- What will people think of me? —>Self-esteem vs. Admiration.

- Will this signal that I am different but the same as everyone? —> Self Actualization vs. Status.

And this changes their Maslow.

a. Will I still Belong? —> Belonging vs. Affiliation.

Knowing fully well that all decisions have consequences while deciding, do I wear the hat of Interdependence vs independence?

An Asian first considers the impact of their decisions on their social ecosystem: An Asian’s identity is inherited at birth. It is the sum total of the groups they are born into—family, religion, caste—and the ones they acquire—family by marriage, workplace colleagues, and friends.

A person born in the West first considers the impact of their decisions on themselves: A person born in the West is an autonomous and independent entity, responsible for only their immediate family. They identify with groups they acquire along the way—college friends or church affiliation—but while making decisions, they mainly consider the repercussions for their own lives and “me-ness.”

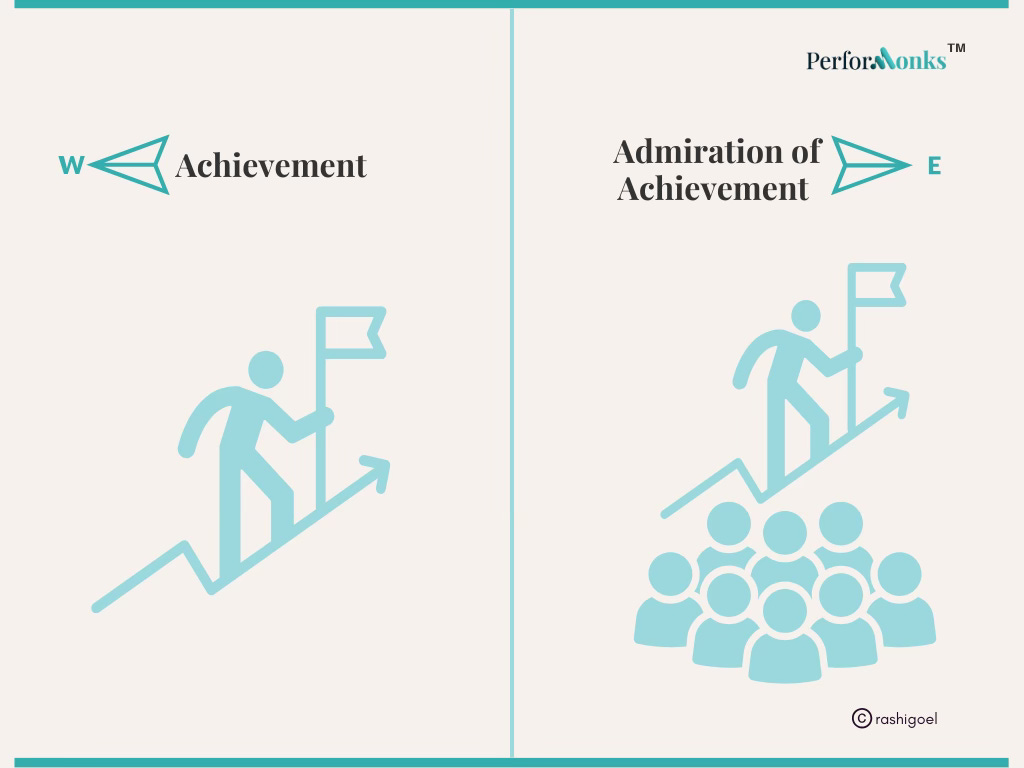

b. What will people think of me? —> Self-esteem vs. Admiration.

I feel good because I have achieved vs. I feel good because I am admired

Both the East and the West are on a quest to achieve more – success, wealth, medals, or education. Whereas the average Westerner will think of their achievement as proof of their excellence, the average Asian will go the extra mile also to seek admiration from others.

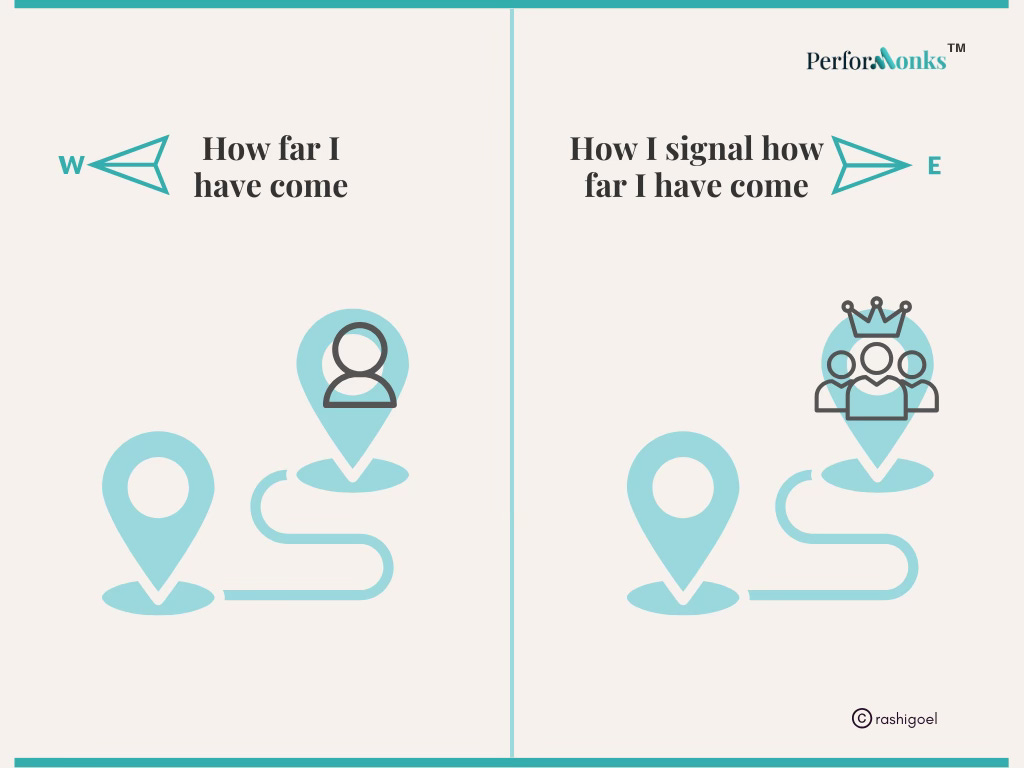

c. Will this signal that I have arrived? —> Self Actualization vs. Status.

How far I have come vs. How I come across

The pinnacle of desire in the West is “to become the best version of yourself.” A painter finally creating their masterpiece or an athlete reaching their peak performance after years of toil will value their journey and celebrate how far they have come.

The average Asian also seeks expertise, but once they have ascended to the top, they expect society to recognize and reward them through positions, awards, and an exalted status. That’s why all conferences start with elaborate lamp lighting and garlanding of the high-status individuals.

This leads to interesting consumer psychology and marketing implications.

2. Marketing implications

a. Saving face

Keeping reputations blemish-free means to ‘save face.’ Missteps might get them thrown out of the ‘Pride’ and starved of social support.

The bridal red: For the longest time, brides in North India wore only traditional red and maroon because they did not want to risk being called ‘fast.’ This all changed the minute celebrity brides wore cream and baby pink.

Marketing implication: High-status folks still have the power to stretch the contours of what’s socially acceptable and set new trends. This explains, to a large extent, the obsession with celebrity endorsements.

b. It’s not just that their sense of self is tightly woven with the group; it pays well, too.

The Patel Motel Empire: The Patel Motel Empire in the US is a perfect example of a social ecosystem that is also an economic accelerator. A NYT article says that Indians own 50% of all motels in the USA, and 70% of all Indian-owned hotels are Patel-owned.

It all starts with one family. They move to a new country and start a business. Once they get successful, they pay the downpayment for a new motel for a cousin. This cousin funds another, so the cycle of paying it forward continues.

”If you look at an example of a domination of an economic niche by an ethnic group, the general story is told in terms of the pioneers and the followers. This is so whether you look at Indian motel owners, Korean grocers, Chinese laundries.”

Thomas Espenshade, a professor of sociology at the Office of Population Research at Princeton University

Marketing implication:

- Community-embedded products can build large businesses, like match-making for one community.

- Every community has its interests, like Patel motels. If a business were to cater to Patel Motels solely – supply all their linen, cutlery, and cleaning products, over time, word of mouth would build a large, sustainable business.

c. Luxury goods signal that they have made it in life.

Asian societies go all out to signal status by consuming luxury goods as if they are going out of style1.

Apple is sold on EMI to aspiring Indians: The iPhone is a luxury product. A significant chunk of its sales comes from EMI schemes and exchange offers.

Marketing implication:

- Asians don’t postpone status. I know managers who can’t afford a new BMW but buy a secondhand one to signal status.

- There is a large market for rental and second-hand luxury brands.

- There is also a market for new masstige brands because a family that can afford a Rs.12,000 handbag will stretch to a Rs.20,000 handbag if it conveys a luxury positioning. For example, millions will make do with a BoAt until they can afford Apple’s ear pod.

As long as we remember that different cultures are different, we can unearth fascinating opportunities for new businesses.

Thanks for reading, and I will see you next week.

1 The Global Luxury Goods Market is expected to be worth around USD 516.6 billion by 2033, up from USD 355.8 billion in 2023, growing at a CAGR of 3.8% during the forecast period from 2024 to 2033. Asia Pacific dominated a 40.2% market share in 2023 and held USD 143.0 Billion in revenue from the Luxury Goods Market. [Source]