In Part I, we looked at how good marketers create solutions with framing heuristics in mind. I had focused on positive and negative framing. Incase you missed it, check it out here.

In this edition,

- I share anchoring bias (closely related to framing bias),

- how great marketers have reframed entire industries,

- what we can do to hack our brains out of these biases.

Anchoring bias

“Sometimes the fault lies not in the decision-making process but rather in the mind of (the) decision maker”

-John S. Hammond

Our brain relies heavily on the very first piece of information it receives (the “anchor”).

This “anchor” then colors all information that follows. That is why, our first impressions of people – their appearance, the city they come from, even their names, unconsciously influence our response.

Our brains tend to anchor to numbers

John S. Hammond, a former professor at Harvard Business School, has researched decision making extensively.

In one experiment, he asked participants to imagine they have $2000 in their bank account, and gave them two options to grow their money.

Option 1- Would you accept a fifty-fifty chance of either losing $300 or winning $500?

Many people refused this offer.

Option 2- Would you accept a fifty-fifty chance of having either $1700 or $2500?

Many people accepted this offer. But if you look carefully, both options are exactly the same! People’s brains anchored to higher numbers, so in contrast, the option quoting lower numbers seemed less attractive.

The power of 9 as an anchor

Surely most of us know that Rs.99 is materially the same as Rs.100. But we still feel happier buying products that end with the number 9. That is why, prices ending in the number 9 are called ‘charm prices’.

The book Priceless talks about charm prices ($49, $79, $1.49 etc.) boosting sales by an average of 24% relative to alternate prices across multiple experiments.

The middle choice as anchor

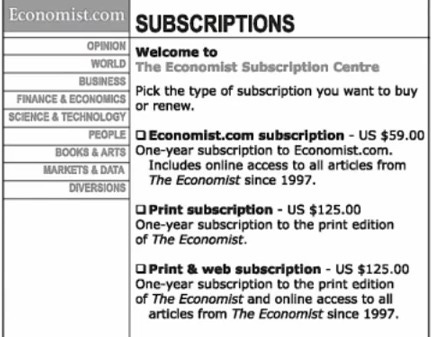

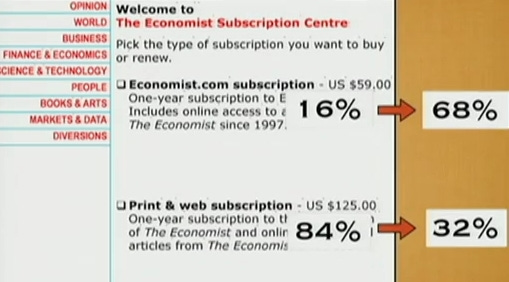

Dan Ariely describes the subscription offer from The Economist in his book Predictably Irrational.

When Ariely asked 100 MIT students to pick one option, 16% chose the first option and 84% chose the third option. Nobody chose the middle option.

So if nobody chose the middle option, why have it?

He removed it, and gave the subscription offer to another 100 MIT students. Most people now chose the first option!

So the middle option wasn’t useless, but acted as an anchor and nudged people to choose the third option, which earned The Economist more ($129 vs $59) and also gave consumers more for the same price!

Great marketers change the frame itself

Good marketers construct messages that elicit responses within the confines of framing bias… but great marketers change the frame itself.

The salesperson who came back from Africa and said that the opportunity was big because nobody wore shoes was doing just that.

By reframing our beliefs, we reset reality. It’s like changing our eye glasses. This helps us shed our limiting beliefs and redundant assumptions.

Reframing identity – Chakh de India

Shah Rukh Khan in this scene from Chakh de India reframes three beliefs for the team.

One, bad behaviors will not be tolerated.

Two, he is the one in-charge.

Three, he reframes identity – India Vs. State. He knows only a shared loyalty to the country would build a cohesive fighting-fit team.

Reframing competition – Pain Balm

I once heard that a dominant Indian pain balm’s proprietor said his brand’s biggest competitor is not the other pain balm company, but the average Indian’s habit of ‘adjusting’ to pain, hoping it will go away. Such reframing sets an audacious vision for the company and expands headroom to grow.

Reframing pain point -Slow Elevator

Everyone complained bitterly about the painfully slow elevator in a multi-storied office building.

The obvious frame is ‘How do we increase the speed of the elevator?’. This involves expensive solutions like replacing the entire elevator system.

The reframe is ‘Long wait time irritates people, how do we engage them better?’. The solution is simple, and inexpensive – mirrors, magazines and a small TV to keep waiting passengers engaged.

Hacking brains

I focus my writing at the intersection of behavioral science, human evolution and marketing. Almost always, unconscious biases explain why we do what we do.

So I end up writing about biases to throw light on the fact that our brains are being hacked constantly, by what we watch, hear and read.

But how do we make sure we reduce unconscious bias in our decisions as much as possible?

By controlling our attention.

What David Foster Wallace says on the importance of controlling our attention is worth mentioning:

“Twenty years after my own graduation, I have come gradually to understand that the liberal arts cliché about “teaching you how to think” is actually shorthand for a much deeper, more serious idea: Learning how to think really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience. Because if you cannot exercise this kind of choice in adult life, you will be totally hosed.”

Source: This is Water

I believe that better humans become better leaders and marketers.

Knowing where our attention is and then digging deeper to understand why, is the best way to become a better human – what I call personal mastery.

Read my philosophy on how personal and professional mastery go hand in hand.

Keep reading!

Rashi