Last week’s newsletter shared a thesis on the fundamental relationship between effort, results, and the role of time → Value = (Output/Input)^Time.

If you missed it, a quick scan will make today’s edition easier to digest. The link.

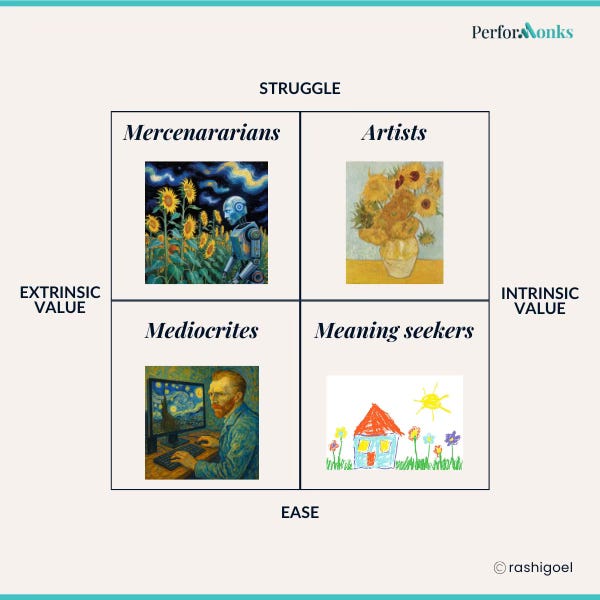

The post-AI world of work will have four types of workers.

Today’s newsletter looks at the top right quadrant – Artists in the age of AI.

- What is artistry?

- Hanzo Hattori and the four ingredients of artistry

- The fifth ingredient – creation never ends

- Unfinishedness – Leonardo da Vinci and Hakusai

- Joy of creation – Vincent van Gogh

- The sixth ingredient – ego death, not hubris

- What does all this have to do with AI?

- The more AI runs our world, the more we will value artistry

- Artistry will collect more currency in the AI-generated sea of sameness

- Artists, not AI, will clear the Lindy test

What is artistry?

Artistry is the single-minded, self-driven pursuit of mastery in our chosen area.

The area is your choice. You might choose to dedicate your life to the narrow subject of studying one strain of bacteria that makes blue cheese. Or you might want to master the entirety of global geopolitics. There is no judgment, as long as you are chasing mastery.

For me, artistry and mastery are two sides of the same coin. The strict definition of artistry covers only ‘the arts’ – painting, prose, poetry, dance, music, singing, calligraphy, pottery. But we know that serious artists chase mastery all their lives. And if you have seen Bruce Lee in action, you know that true mastery resembles art.

That’s why in this article, I use both words interchangeably.

Hanzo Hattori and the four ingredients of artistry

In Kill Bill, as Beatrix (Uma Thurman) prepares to destroy her enemies, only a Hanzo Hattori Katana (sword) would do.

This clip (13 minutes long, but savour-worthy) captures all the nuances of artistry that I would need a lifetime to crystallise in words. THE VIDEO LINK.

Nonetheless, here’s an attempt.

- Lifelong commitment to mastery: Hanzo Hattori has spent his entire life perfecting just one thing. Sword-making.

- Spiritual meaning: To him, his craft is sacred. The reverence is palpable – Beatrix seeks permission before she touches the katana. Even the bald, annoying guy pipes down and plays a respectful ceremonial role during the sword gifting.

- Intrinsic value: Hanzo Hattori is not out to make a quick million. He lives simply, humbly, but the swords have pride of place in a run-down attic. Only the worthy can possess his Katana. If he does not believe you value his work, no amount of money will coerce him to part with it.

- Those who know, know: Hanzo Hattori’s fame is not loud, it whispers into the ears of only those who have earned the need to know.

There are two more ingredients that this clip misses.

The fifth ingredient: creation never ends

Two mental models compel artists to create endlessly.

Mental model 1: Artists live in a perpetual state of unfinished-ness.

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci painted The Mona Lisa between 1503-1506, but then continued to work on it until 1517. Had he lived longer, I would bet good money that he would have continued to tinker with it.

Hakusai

Even though The Great Wave off Kanagawa is “possibly the most reproduced image in the history of all art,” its creator, Hakusai, felt he still had not attained mastery.

Many years before his death, Hokusai said this:

“From the age of six, I had a passion for copying the form of things and since the age of fifty I have published many drawings, yet of all I drew by my seventieth year there is nothing worth taking into account.

At seventy-three years I partly understood the structure of animals, birds, insects and fishes, and the life of grasses and plants.

And so, at eighty-six I shall progress further; at ninety I shall even further penetrate their secret meaning, and by one hundred I shall perhaps truly have reached the level of the marvellous and divine.

When I am one hundred and ten, each dot, each line will possess a life of its own.”

Vincent van Gogh

Mental model 2: Or they create simply for the joy of creation.

Van Gogh did not paint just one Sunflowers canvas. He painted many. He started painting Sunflowers in 1886 and then continued for the next few years.

Why? Because it became his identity – when everybody else was painting peonies, only he was painting sunflowers. Van Gogh famously said to his brother, “the sunflower is mine.”

More than that, painting sunflowers gave him joy. Van Gogh wrote to his brother.

“I’m painting with the gusto of a Marseillais eating bouillabaisse [Provençal fish stew], which won’t surprise you when it’s a question of painting large Sunflowers.”

Mastery is as simple as that. We chase the joy of creation, and stumble into mastery.

The sixth ingredient – ego death, not hubris

Van Gogh became one with sunflowers. I believe artists become one with their craft. This is impossible without ego death.

There is no hubris in mastery. Just a humble acceptance that we are vessels for what the divine, unknowable, eternal, universal creative energy wishes to manifest through us. Nothing more, nothing less.

The Greeks even had a word for these spirits of creative genius, “Daemons.” They believed that Daemons hovered all around us and waited. They waited and refused to share their genius until they were convinced that we had sweated enough, struggled enough, and had shown up for our saadhana (intense, disciplined pursuit of something) enough number of times. That’s when they poured their genius into our fingertips, our paintbrushes, our vocal cords.

If you remember some thing you wrote, some campiagn you led, or some insight that tumbled out of your mouth and you wonder, “where did that come from?!” Chances are that for those microments, Daemons were working through you.

That’s why when Hanzo Hattori says, “If on your journey, you should encounter God…God will be cut,” I discount this as Hollywood puffery, necessary to convince us that Breatrix was armed with the world’s best katana for the tough battle she was preparing for.

What does all this have to do with AI?

Everything. Because true artistry blooms in a climate where AI goes to die.

when we embrace struggle and don’t delegate it to machines,

when we keep showing up even when there is no positive feedback from the external world,

when we create a space for a mystical universal energy to flow.

That’s why,

The more AI runs our world, the more we will value artistry

Apart from the fact that Hanzo Hattori personifies mastery, there is a second reason why I picked him.

Japan is the closest living microcosm of what an AI-operated world might look like. Driverless trains, conveyor belt sushi, toilet seats that lift and close by themselves, and vending machines that serve piping hot ramen. Feels like magic!

Paradoxically, when technology starts manufacturing magic, humans are valued more for their artistry. That’s why it makes sense that in Japan, artistry is as serious as religion.

Swordsmiths learn how to fold steel thousands of times to create katana blades. Some masters spend over a year to perfect a single sword.

Sushi apprentices spend years just learning to cook rice properly before they are even allowed to touch fish.

Japan protects “intangible cultural assets” – Living National Treasures 人間国宝 Ningen Kokuhō (people who have achieved mastery) – like we protect UNESCO sites.

Artistry will collect more currency in the AI-generated sea of sameness.

Dan Pink was especially prescient in his 2006 book, A Whole New Mind. He said that since automation will take over all repetitive, read ‘left brain tasks’, humans with evolved ‘right brain skills’ will find success.

This makes sense because when AI creates from what already exists, there will come a time when all new ideas will start to look like the old ones.

A quick read through on LinkedIn will show you what I mean.

This rancidity from ideas recycled many times over will only be washed away with the fresh water of an artist’s original genius.

Taste, judgment and curation will become critical.

We revere artists because they can do things we can’t even dream of. They have taste, judgement, and originality.

Masses who use AI to add to the noise will need taste-makers to tell them what to like. And why. That’s why careers that involve curation of ideas, judgment and a refined taste will enjoy high status.

Artists, not AI, will clear the Lindy test.

Knowledge and ideas have a half-life – The Lindy Effect. The Lindy effect says that the future lifespan of an idea will be at least as long as its past life.

The faster we consume, the more we get jaded. In a high-consumption society like Japan, new products – Sakura Kit Kat, Chocolate Coated Potato Chips – have a shelf life of only 15 days to a month, while the centuries-old taste of Umami and Matcha remain daily staples.

When the same ingested body of ideas is regenerated billions of times, they fade away like yet another Cola flavour in Japan.

Case in point, Studio Ghibli is forever, but the billion Ghibli selfies that flooded our social media two weeks ago are nowhere to be seen as I write this.

Masters who create for the joy of creation will continue to create.

That’s why original content will become precious because people, weary of manufactured creativity, will hunger for flawed works that smell of human sweat and grime.

Thank you for reading.

I will see you next week.

Sources

- Wood, Patrick (20 July 2017). “Is this the most reproduced artwork in history?”. ABC News. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Great_Wave_off_Kanagawa

- https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20140120-van-goghs-flower-power

- Elizabeth Gilbert – Daemons

More ways to connect

- Connect on LinkedIn

- Read the archives

- Subscribe to this Newsletter