In season 6 of The Sopranos, Tony Soprano gets shot. After he returns from the hospital, he knows that as a mob boss, even a whiff of physical weakness will be like blood in shark-infested water, and his days will be numbered.

He has to reassert his dominance. And fast. He decides to pick a fight.

In the video, we see Tony taking stock of the guys around the table for the pretend fight he plans to have. He can pick any of them. The nephew wouldn’t fight back (out of respect), but he is not worth winning against (he’s not well-muscled). The others are lifelong friends and would fight back, but they are old. Again, beating them up would also not prove Tony’s strength. Worse, if they get upset, they might leave which would really put a dent in the business.

So what does he do? He chooses Perry.

This is brilliant for three reasons. Perry is the youngest and strongest, so by whipping Perry’s arse, he would have asserted his strength beyond doubt. Perry is also the new guy. As a new guy hoping to curry favor with the mob boss, he would hold himself back in the fight. Lastly, even if Perry were to get upset and leave the mob, the loss would not impact operations.

Win-win-win.

Does this take a toll on Tony? Yes. After the fight, he goes to the loo and vomits blood. Is it a short-term sacrifice that would pay off in the long run? Ooohhhh yes.

As a ‘distressed brand,’ he manages to (literally) fight his way back to dominant status.

Tony was strategic—he risked his health, and he risked being seen as unhinged for a few weeks to secure his future.

Brand strategy boils down to strategic choices

Marketers have to choose between options that seem similar on the surface.

E-commerce site for fashion or e-commerce for beauty and fashion?

Script A or script B?

100% sustainable plastic tubes or 50% sustainable plastic tubes?

It’s terrifying because there are no right or wrong answers.

How do we choose? We choose whatever takes us closer to our Northstar – our brand vision.

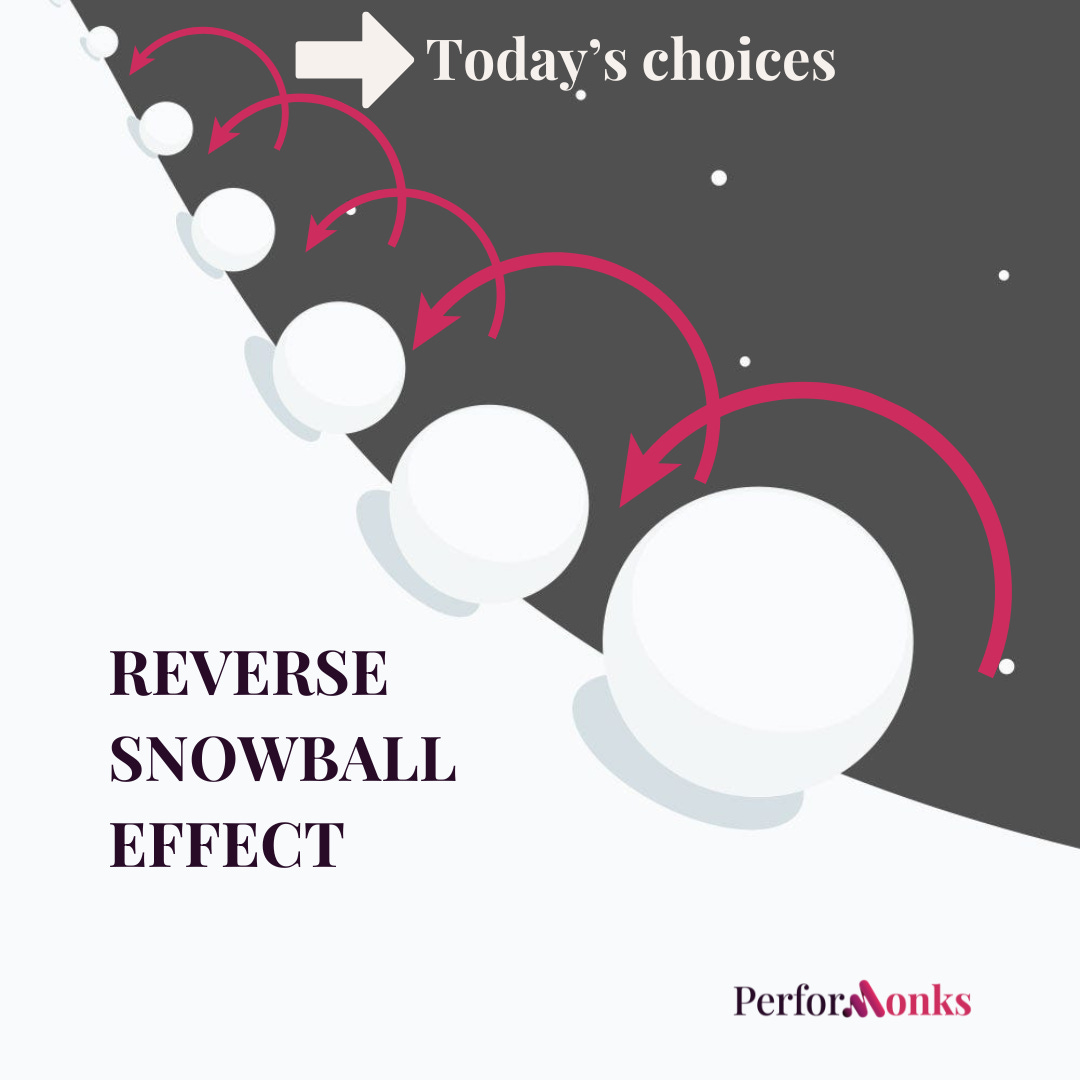

Think of it like a snowball effect in reverse

Brand Vision is an imagined future—a future in which the brand would have made all the difference it has set out to make.

Think of it like a snowball effect in reverse. First, imagine what the world would look like in the future after the brand has accomplished everything it has set out to do. This could be body positivity for Dove, fit and active humans for Nike, a germ-free India for Lifebouy, or songs in every pocket for Spotify – this is the giant snowball we want to end up with.

Then, retrace your imagination all the way back to the present day. And think about all present-day choices that, like fistfuls of snow, add up to a tiny snowball, ready to be rolled down the proverbial slope of time.

In other words, what we want the brand to stand for in the future determines where the brand sits in the present.

When we apply this lens, many inspiring examples come to mind. Let’s look at Patagonia, General Mills, and CVS.

Patagonia: don’t buy new, repair the old

Patagonia imagines a world free of landfills choking on discarded clothes, so it willingly sacrifices revenue. It encourages consumers to repair old jackets instead of buying new ones, and also offers to repair sold jackets free of cost.

General Mills: share technology freely

In the 1870s, cereal-producing mills were called ‘dust collectors.’ Cereal was produced by milling wheat to make flour and then heating it. Flour dust choked the exhaust fans and circulated throughout the factory like the relentless sandstorms of the Sahara. If not cleared, it could become a fire hazard.

Sure enough, one of General Mills’ factories blew up one evening, and all 18 workers died tragically. [Source]

The company took care of the employees and constructed a new factory, as they would. Spurred on by this tragedy, their engineers invented a safer machine. Instead of locking in the technology through patents, the founder shared it freely with the competition so that no more lives were lost.

CVS: discontinue products not in line with vision

In September 2014, the US drugstore chain CVS rebranded itself as CVS Health. Its corporate purpose was ‘Helping people on their path to better health.’

They reverse-snowballed this vision into a present-day ballsy move – they stopped selling cigarettes. This would lead to a potential $ 2 billion revenue loss.

Do you know why strategic sacrifices are strategic? They may lead to a dip in the short term, but they pay back many times over. CVS’s stock price fell from $66.11 to $65.44 per share one day after the announcement but recovered the next day. A year and a half later, the stock had doubled to $113.65 per share – the highest ever. [source]

But I must point out an exception. Not all sacrifices are strategic. Some sacrifices are necessary just to survive.

Sacrifice for survival’s sake is not strategic sacrifice

In Guy Ritchie’s film The Gentlemen, Matthew McConaughey plays a drug lord (Mike). When Jeremy Strong (Matthew) tries to steal his business and disrespects his wife, Mike locks Matthew in a meat locker.

That’s not all. Matthew can buy his way out of the meat locker, the price is a pound of flesh – a pound of flesh cut from his body. ‘Not a gram less,’ Mike clarifies.

Matthew does not have a choice. He pays for his survival with a pound of flesh.

That’s why, dear readers, brands that recall products when something goes wrong (car safety or alleged wrong ingredients in food, etc.) are not making strategic sacrifices.

They’re only paying the price of survival.

Career choices also involve strategic trade-offs

When Person A lets go of a plum job in another city, they make a strategic sacrifice. They trade off career growth and more money in the short term for a more fulfilling family life in the long term.

Person B might take up said job in another city because they believe the extra money will smoothen the ride for their family.

Person C might take up said job in another city because they know that, more than anything else, not meeting their true corporate potential will lead to a lifetime of regret.

There are no right or wrong answers. Just choices that snowball into our future identities.

Thanks for reading!