“If they jump in the well will you too!?” I can bet good money that all Indian mothers have said this to their kids at some point. Our mothers had a habit of dismissing our demands as peer pressure. Goa holiday, studying arts over medicine, even buying expensive gadgets were mere nuisances that had to be swatted away like flies.

The irony was that our mothers overlooked our mimetic desires to feed theirs!

Mimetic desire, regardless of what we call it – peer pressure, herd mentality, FOMO, or Maya (illusion), is real.

Rene Girard’s mimetic desire theory

A French anthropologist and Stanford Professor, Rene Girard, developed the idea of Mimetic Theory. He said that mimetic desire unfolds sequentially.

I share the five sequential steps and illustrate each with stories that resonated with me.

1. At the core of mimetic desire lies the fact that we are imitation machines: Our brains are wired with mirror neurons. So, unknown to us, what we see, hear and read influences what we want. As a result, we end up wanting what others have. This means that our independent thinking does not drive our desire.

Scientists learnt of mirror neurons in 1992. They were studying which neurons controlled which body movements on a monkey. One day, a researcher was eating an ice cream cone in the lab. The monkey was watching the scientist and was not moving. Yet, those very neurons that would have fired had the monkey moved his hand up and down to eat the ice cream were activated! These were mirror neurons in action.

Mirror neurons are a byproduct of evolution and helped us survive. If we saw a fellow caveperson running away, we followed within a heartbeat. Had mirror neurons not existed, the pause it took us to process the presence of a predator might have cost us our life.

If we read or hear the word ‘cinnamon’, the same part of our brain that lights up when we smell cinnamon in real life, gets activated. And then our body also wants to smell real cinnamon.

This is probably why the minute we see a picture of a burger, our diet goes for a toss.

This brain feature has been put to good use by brand communication experts. Food or beverage advertising is incomplete without a ‘consumption’ shot. When I worked at Coke, there was a global mandate to have a drinking shot on every poster. So, we spent our time trying to innovate new stylish ways to drink from a glass bottle each year!

Good social media influencers engage with the product they are promoting instead of just talking about it, and that makes a big difference. Brands that invest in attractive product shots on their e-commerce page enjoy higher sales conversions.

Mirror neurons can and do fuel bad actors. It is said that we are a byproduct of the five people we spend most of our time with. If these five people are couch potatoes, there is a high chance we will become one too.

On the other hand, we can use mimetic desire for good. We all know that kids learn through mimicry. The best way to influence good behaviour and instill good values is by modelling better behaviours. Two campaigns use this powerful insight in different contexts – Children see, children do and Strings.

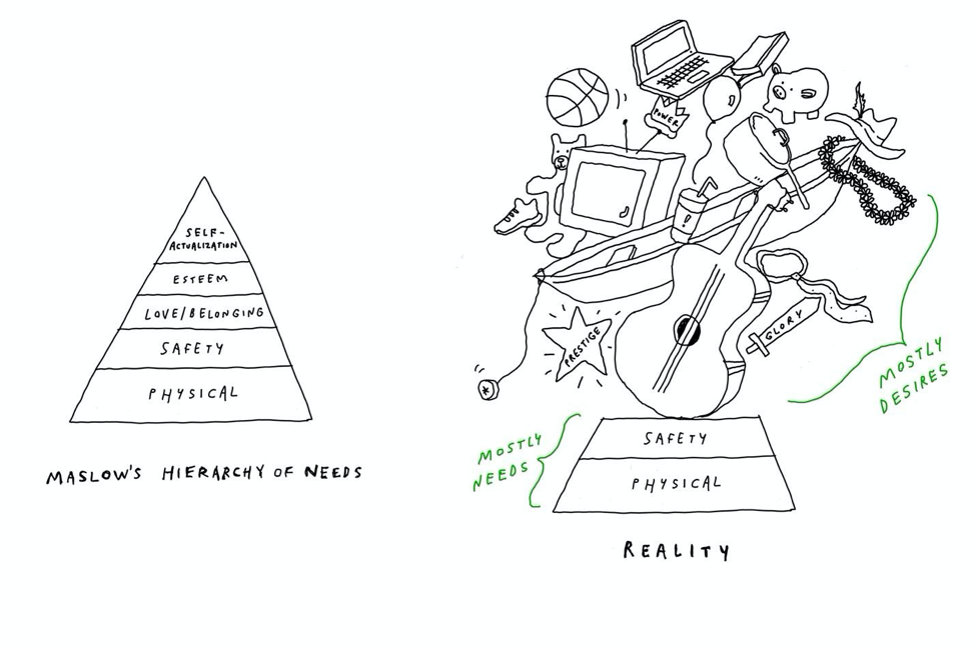

2. Our desires are not fundamental needs: We are instinctively driven to satisfy our survival needs. But once these needs are met, we start craving things that we don’t need, only because others have them. We convince ourselves that every shiny new bauble we chase is life-critical!

Desires can be manufactured. The first-ever PR campaign created a desire for cigarettes amongst the unaddressed market of women. During the first world war, cigarette smoking amongst men peaked, but it was still socially unacceptable for women. However, while men were at war, women stepped out of their households and took charge of the reigns of the economy. The manufacturers of Lucky Strike approached Edward Bernays (credited with the invention of the field of Public Relations). He designed the ‘Torches of Freedom’ campaign. During the Easter parade, Bernays’ secretary (Bertha Hunt) stepped out, stylishly smoking a cigarette. She was the right choice to model cigarette smoking – a woman next door, socially credible and yet not too glamorous. The campaign added mimetic meaning to cigarettes as expressions of strength and freedom.

While PR/Marketing are desire-generating machines, the moral and health hazards of desires have changed over time. In the 20th century, cigarettes, much like fatty and sugary food, were enjoyed by all and were symbols of upward mobility. The moral underpinning of marketing is to promote responsible consumption (I have written about how marketing can be used for good here), and more importantly, to innovate products that are good for us. But I digress.

Mimesis is efficient. When we search for a new song, a book to read, or a new movie to watch, it is more efficient to go by rankings and reviews. The flip side to this is that we may go through life just following a crowd, without liking anything original (hence ‘risky’) or without discovering our taste.

People like a song more when they think other people like it too. Sociologists Matthew Salganik and colleagues at Columbia University, created a website with 48 songs by unknown bands. They recruited 14,000 people to rate and download the songs. One group was ‘socially influenced’, which means they could see names of songs, bands and the number of times they had been downloaded. The second was left to their individual choices and only saw the names of songs and bands.

Both groups more or less liked the same songs. But those who could see the number of downloads tended to give higher ratings to the songs that had been downloaded more. This snowballed into getting some songs to the top of the charts, while others got left behind.

There’s more to this story. The ‘socially influenced’ group was divided into eight different ‘worlds’. Each world had a different download history. As it turned out, different songs made it to the top of the charts in different worlds. What blew my mind was that some songs were on top in one world and almost at the bottom in others!

This means that ‘taste-makers’ hold immense power over defining our taste and in making or breaking ‘stars’. This brings us to the next step in the mimetic theory sequence.

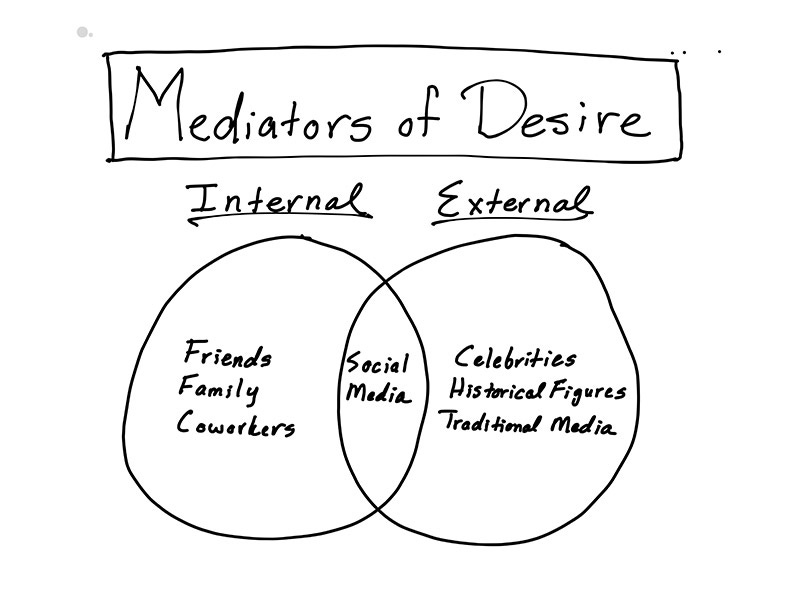

3. We let aspirational role models influence what we desire: These role models could be within our intimate orbit of family, work and social life, or in the larger orbit of media, culture and celebrities.

We are competitive rather than aggressive…We literally do not know what to desire and, in order to find out, we watch the people we admire: we imitate their desire.

Rene Girard

Brands have partnered with celebrities to change their fortunes. One of the earliest associations was for Pepsi and Michael Jackson in 1984. Pepsi was not doing well, so they signed up MJ as a counterpoint to Classic Coke. MJ was the latest youth icon and so by extension, if MJ drank Pepsi, the ‘new generation’, i.e. youth wanted it too. When Pepsi entered India, they replicated this exact strategy and signed up Remo Fernandes + Juhi Chawla.

Critics and tastemakers ‘infect’ our taste. The infectious nature of mimetic desire is most visible in the fashion and beauty world. Celebrities and models wear the latest fashion wrapped within an attitude. These looks become aspirational culture for us. When these fashions are diffused to us at prices we can afford, we jump to buy them. Mimetically, we buy not just the fashion, but also the attitude and lifestyle.

This clip from The Devil Wears Prada explains so well how fashion is created and diffused.

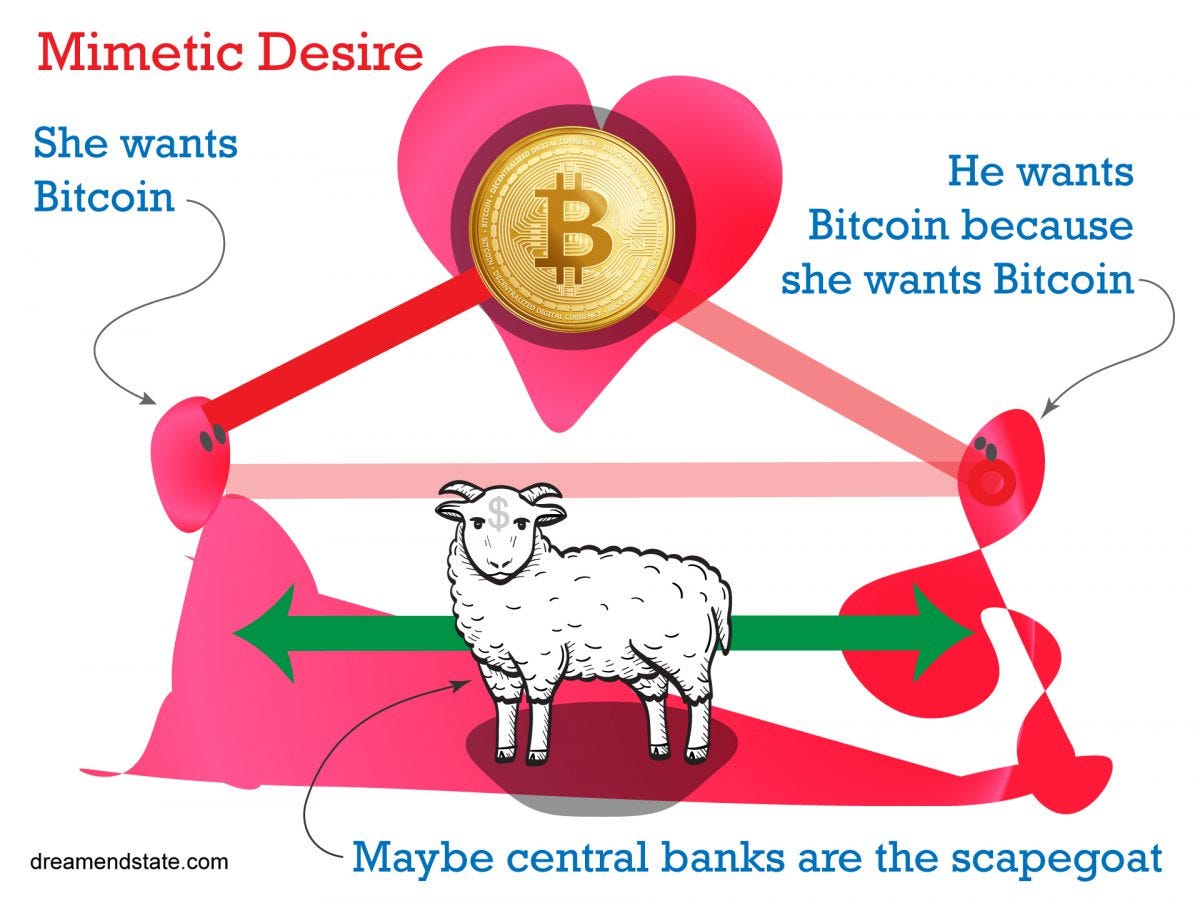

We are swimming in the sea of sameness. We find ourselves listening to the same songs, wearing the same fashion, and even buying the same stocks to cause a financial bubble. We start telling ourselves that we are not complete unless we also have what our role models have. Girard calls this Acquisitive Mimesis- we all want to acquire fame, money, and the next promotion … all of these are scarce objects.

This desire for scarce things leads to competitiveness, and we become rivals.

4. We all end up wanting similar things and this leads to Mimetic Rivalry: Office politics, casting couch, bribery, corruption, and even wars and religious crusades are a result of scarcity-fueled mimetic rivalry.

Social media is accelerating mimetic rivalry. We have organized ourselves into multiple micro-communities on Facebook pages, Whatsapp groups and Substack. These tribes organize around self-reinforced beliefs and strong points of view. Anybody with a different belief becomes the ‘other’. And this leads to a lot more mimetic rivalry.

New platforms like BitClout are built on blockchain and assign a Bitcoin value to our social media profile. Are we entering the dystopian world that Black Mirror fictionalized, where our reputations rise and fall like stock prices?

Mimetic rivalry can also create value. Adidas and Puma, Lamborghini and Ferrari were born out of business rivalries and as a result, have created innovation and value. In 1963, Ferruccio Lamborghini was a tractor manufacturer. He owned a Ferrari but was unhappy with its clutch. He especially visited Enzo Ferrari to give him feedback. Ferrari dismissed him, “Let me make cars. You stick to making tractors”. Enraged, Lamborghini started manufacturing cars.

Adolf and Rudolf Dassler – brothers and bitter rivals, built Adidas and Puma. Once, they both wanted to sign on Pele. But they struck a “Pele Pact”, to not get into a bidding war, as it would be a lose-lose game. Puma tricked Adidas by using a loophole. For just $120,000, they requested Pele to briefly stop to tie his shoelaces before entering the field. The company also paid the cameraman to zoom in. The whole world thought Pele wears Puma and sales rose.

5. To dissolve conflict from Mimetic Rivalry, we sacrifice Scapegoats: Prolonged rivalry at scale could lead to intense ugliness, so we dissipate tensions by finding a common enemy to blame for our discontent. The scapegoat is ‘punished’, to calm down rivals.

Girard says that in extreme cases, the scapegoat is murdered (e.g. Jesus Christ, Julius Caesar). Or the scapegoat serves a period of ‘time out’ (e.g. Ram & Sita on exile). Oftentimes CEOS, Presidents and senior politicians are scapegoated to assuage the masses or to win elections. The cancel culture, in my opinion, has now become a socially accepted way to release pressure.

Scapegoating non-users of a product is a common communication tactic. The anxious woman whose husband’s shirt is not as white as the one who uses Rin. The ‘before-after’ for acne-prone teenagers, dark girls or smelly armpits. Making the non-user the ‘other’ and somehow ‘lesser’ is common and makes consumers feel that they would enter the elevated inner circle of the brand by buying the product.

Luke Burgis has authored “Wanting- The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life”. In this book, he discusses Girard’s ideas in the context of today’s world. He says the problem with mimetic desire is that we start living an unintentional life. He recommends that we start moving towards an anti-mimetic life.

An idea to start 2023 with – live an anti-mimetic life

Like Pavlov’s dog, we chase one fad and then the next. There is no end to the mindless pursuit of desires. The next million dollars, the next promotion, the bigger car, even the next 100 books we will read and blog about…. It’s never-ending and stressful.

I propose three mindset shifts that could take us closer to an anti-mimetic life.

1. Resume virtues vs. eulogy virtues: David Brooks, in his book, The Road to Character, says that we spend our lives chasing“resume virtues” – virtues that lie along the ladder of success. This ladder is endless and no matter how high we climb, there will always be someone ahead of us. He suggests we could instead pursue “eulogy virtues”. Eulogy virtues are positive actions others remember us by.

2. Listen to the internal compass over external report cards: if our self-worth is linked to our wants, this is a strong signal that we have become slaves to external report cards.

Another signal is if we find ourselves thinking of things we should want, do or be.

If we really truly pay attention to our inner compass, we will find that our internal compass and eulogy virtues align.

I can’t but help share this clip of Mr.Fred Rogers. It is so clear that he was guided by his inner compass.

Chef Sébastien Bras owns Le Suquet restaurant in Laguiole, France, a three-Michelin star restaurant. In 2018, he asked the Michelin Guide to stop rating his restaurant. The chef realized that in the quest to maintain his three Michelin stars, he had stopped experimenting with new dishes for fear that the Michelin inspectors might not like them. He realized he had become a chef to share ingredients from the Aubrac region, not to become a slave to a rating system.

It was easy for the chef to walk away from Michelin after he had got three of them. That’s where the third mindset shift comes in.

3. Believe we have enough: We need to define how much is enough. Here, we could decide to be like Rockefeller or like Heller.

John D. Rockefeller was the richest man on Earth. When asked by a reporter, “How much money is enough?” He responded, “Just a little bit more.”

One time, Kurt Vonnegut teased Joseph Heller at a party, that their host, a hedge fund manager, had made more money in a single day than Heller had made from Catch-22 over his lifetime. Heller responded, “Yes, but I have something he will never have — ENOUGH.”

In pursuit of our mimetic desires, if we understand why we want something by asking ourselves three three questions –

- what eulogy virtue will this lead to?

- is it in service of an internal compass?

- when will we feel we have enough?

and only then decide if we want to proceed, we might end up living more wholesome lives.

My journey to write what I learn and to discover what I know will continue in 2023.

Happy New year and see you on the other side!

Resources:

- Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life by Luke Burgis

- Compendium of videos on Mimetic Desire

- https://www.shitididntknow.com/posts/2019-12-30/mirror-neurons-mimetic-theory

- https://psyche.co/guides/how-to-know-what-you-really-want-and-be-free-from-mimetic-desire