In the previous edition – “Have you won the luckttery?”, we looked at the significant role luck plays in our success.

Lately, I have become obsessed with luck, destiny, fate… what we can control and what we don’t. Today, I share,

- what I have learnt about the fascinating interplay between luck and skill.

- why only oner time do we know for sure if success is skill-led or a result of luck.

- and why we need to decide with some degree of rationality, where our work falls on the skill-luck continuum.

Luck = Outcome – Skill

A guy buys a lottery ticket with ‘48’ as the last two digits and wins millions of dollars. When asked why he bought a ticket with those very digits, he says the number ‘7’ appeared in his dream several nights in a row. And because ‘7 multiplied by 7’ is ‘48’, he bought the ticket. (I am told this is a true story!).

This is an example of pure dumb luck!

Barring extreme examples like this, most failures and successes are combinations of luck and skill.

Michael J. Mauboussin has done a deep study of luck vs skill in his book, The Success Equation. (Word to the wise: if you read only one book this year, let it be this one). He says, “Luck is what we are left with when we subtract skill from the outcome.”

Problem is, we don’t think about our life and work in the form of this formula. On the contrary, we have a rather self-indulgent view of skill and luck.

We believe ‘Heads I Win, Tails it’s Luck’.

We attribute our success to hard work and talent. And we blame bad luck for our failure.

We think exactly the opposite when it comes to others – obviously, others are successful because they lucked out, but they fail because they are incompetent!

We can work hard and be highly skilled, but still fail. We can also be lazy and bad at what we do but still succeed. That’s why Morgan Housel reminds us to not write off people who have hit rock bottom and only cautiously admire people who are at the top.

He also tells us to be gentle with ourselves.

“But more important is that as much as we recognize the role of luck in success, the role of risk means we should forgive ourselves and leave room for understanding when judging failures.”

—Morgan Housel

Even if we acknowledge that luck plays snakes and ladders with our life outcomes, it is difficult to rationally predict how much skill and how much luck has gone into the recipe for our success. That’s because there are a million skill and luck combinations.

In real life, the equation expands into this murkiness.

Let me illustrate this through these situations.

Situation 1: A state cricket champion keeps getting bowled out in the trials and does not make it to the national team. His life scenarios could be:

- Skilled but unlucky: maybe he is a skilled cricketer who’s having a bad week – a diamond in the rough. Let’s give him a chance – through deliberate practice and excellent coaching – he could be our next Dhoni!

- Unskilled and unlucky: it takes a very high degree of skill to make it to the national cricket team. Maybe the player is the best within the smaller competitive set at the state level but is just not cut out for the national level. Drop him, don’t waste any more time.

- Unskilled and lucky: the player knows someone on the selection board and gets selected anyway. Coaching improves his game, but not by much. Over time, after playing enough matches badly, he leaves the team in disgrace.

Situation 2: An early employee of Infosys sells off his shares to fund his MBA and loses out on serious wealth. He could be:

- Skilled and lucky: Since he is skilled enough to get into Infosys, an MBA only adds to his skill-set. After his MBA, he joins a pre-IPO startup and makes even more money than he would have made from the Infosys shares. This was a necessary investment into a prosperous future.

- Skilled and unlucky: this was a judgement error. After his MBA, he has a long corporate career, but he never makes the kind of money his Infosys shares would have given him.

- Unskilled and lucky: He was lucky that he got a job at Infosys so early on. He is best as a product manager and was out of his depth in the business world. He reaches middle management, and even makes money, but never the kind he would have made had he stayed invested in Infosys.

- Unskilled and unlucky: He was lucky that he got a job at Infosys so early on. He is best as a product manager and was out of his depth in the business world. When the expectation-reality gap became unbearable, he turned to alcohol. He died young, bitter and alone.

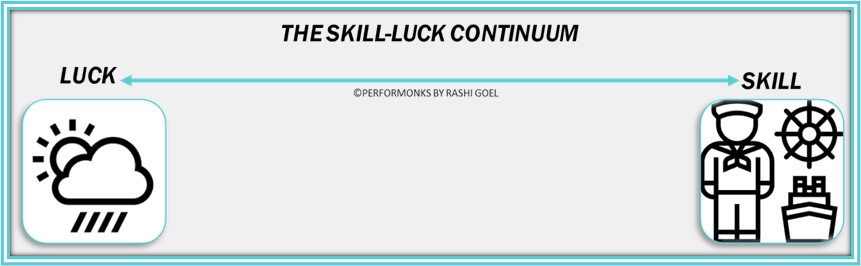

Knowing where our work falls along the skill-luck continuum helps us make better sense of our upsides and risk profile

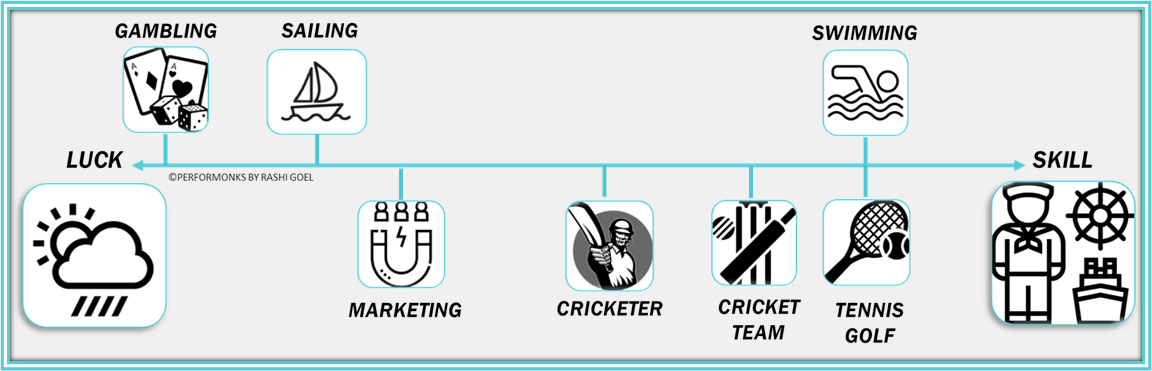

Skill is analogous to sailing. Sailing is a skill because it can be learnt and taught. There are good sailors and bad sailors. If one has talent, one can even become a great sailor through deliberate practice. (I have written about the 10,000-hour rule of skill-building here and here.)

Sailing conditions – wind, weather and ocean currents are like luck -they have a huge impact on the outcome. Yet, they are unpredictable and no sailor can control them.

Sailors and sailing conditions are lifelong frenemies. But the best sailors maximize return on luck. They adjust their timing, route and strategy so they are sailing in the direction of the wind, not against it. By making the wind work for them, they maximize their return on luck.

There is no doubt that sailing requires a lot of skill, but a tsunami could sink even the best sailor with the strongest ship. That’s why good sailors know better than to ‘tempt fate’. When conditions are not safe, they drop anchor and wait it out.

An interesting anecdote here is that of Christopher Columbus. During the 15th century, all sailors sailed against the wind direction because they did not want to go too far away from land. But when Columbus set off to find India in 1492, he purposely sailed with the wind to get to far-off lands as fast as he could.

Therefore, it seems that sailing might be more impacted by random luck, so it would sit to the left side of the skill-luck continuum.

A swimmer in a tournament is not subject to as many random events of luck as a sailor in the ocean is. Therefore, a swimmer could, through deliberate and consistent practice, tame bad luck. Just like Michael Phelps did.

Michael Phelps trained for bad luck. Swimming ‘blind’ was a regular part of his practice. He often swam in the dark. Sometimes, just as he jumped into the pool, his coach used to tear off his goggles. At the 2008 Olympics, he was in his last race – 200m butterfly. But a few strokes in, his goggles started to flood with water. Immediately, his ‘bad luck training’ kicked in and he still won the race.

“My goggles fill up with water… I counted my strokes”

– Michael Phelps on how he swam ‘blind’ at the 2008 Olympics

We start to understand relative placement on the skill-luck continuum when we compare swimming and sailing. Luck plays a bigger role in sailing vs. swimming.

We could debate the exact position sailing occupies along the continuum. Maybe a little more skill and a little less luck? We won’t know the exact answer right now, but we can tease out the skill-luck ratio over time.

The paradox of luck, skill and time

In Hindi, there is a saying, “doodh ka dhoodh, paani ka paani”. It means that when milk and water are mixed, for justice to be served, we have to know how much water is there in the milk.

I think this applies to success and failure – real skill does not stay hidden for long. When there is a huge skill mismatch – Tiger Woods playing against me – it will take only one game to separate the ‘water from the milk’ 😊

Even Tiger Woods goes through rough patches. So even though he may not do so well in some, his track record across many many matches will be better than less skilled golfers.

This means that in activities that have a higher skill component (golf or tennis) – skilled performers rise to the top faster and stay there longer. For instance, Roger Federer has spent 237 consecutive weeks (4.5 years) as No.1, and a total of 310 weeks (almost 6 years). Source.

On the other hand, in activities that have a higher luck component, it takes much longer to smoothen the jagged edges of luck. Also, there are many upsets at the top because skill alone does not guarantee success over time.

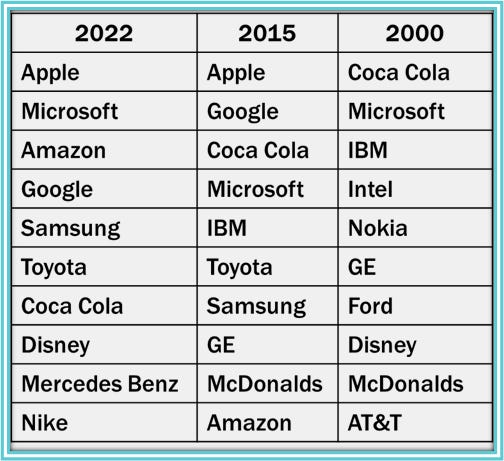

This volatlity is proven when we map the top 10 brands as per Interbrand over 22 years. AT&T, IBM, Intel, Nokia and GE disappeared, while all other brands are see-sawing. Apart from Apple, because Apple. This proves that luck plays a greater role in marketing than in tennis.

Let’s move on to cricket.

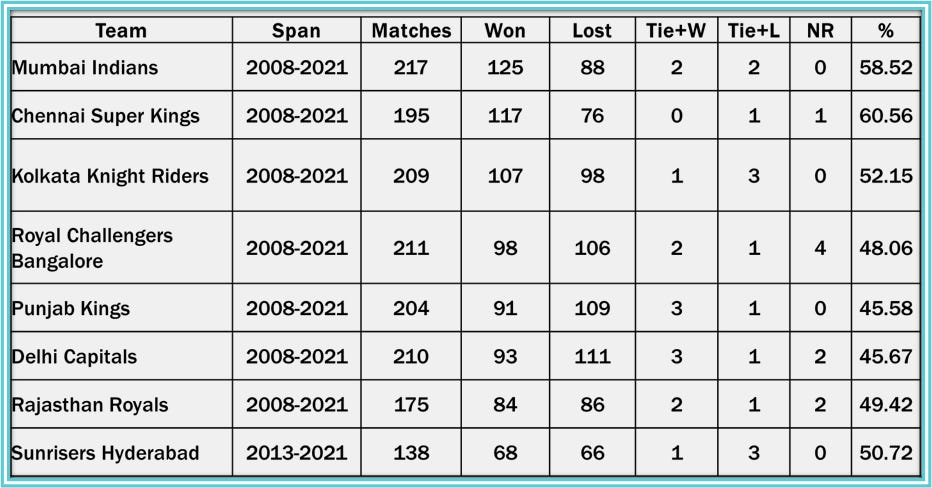

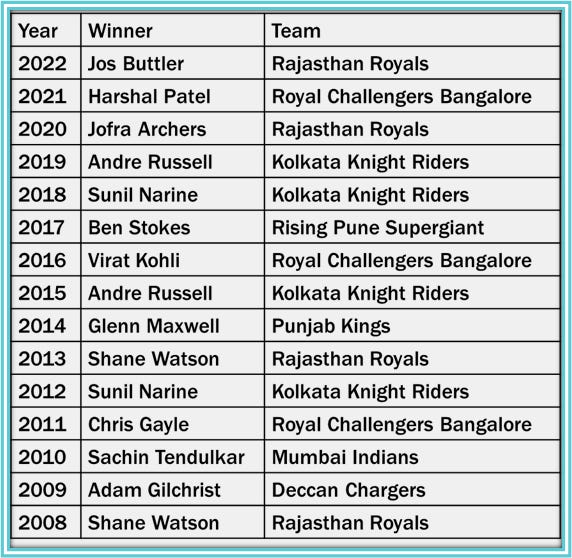

When we compare the ranking of IPL teams vs IPL players, we see an interesting paradox. Over 13 years, Mumbai Indians have won the most matches, but Chennai Super Kings is the more skilled team because they have the highest win percentage. When we see the consistency in the top 2, we could conclude that skill plays a bigger role in IPL cricket than luck.

But the most valuable player rankings show that the top cricketer has changed every year! Even more surprising is that no CSK player has ever been top-ranked, and only once has a player from Mumbai Indians made the cut.

It appears that success or failure in cricket is driven more by team skill, while an individual player’s success is driven relatively more by luck. Makes sense when we think about it for a second. Since this is a team sport, the skill of one player could get cancelled by the luck or the skill of another player (e.g. Dhoni hits a six, but Kohli catches it). So, the outcome for a team is impacted by how well the team plays together rather than individuals playing for themselves.

All this leads to this chart that places all activities we have discussed along the skill-luck continuum.

This exercise has taught me how important it is to understand where the work we do falls along the continuum. Only once we understand this, can we start to get strategic about how long a game to play (only over time does skill triumph), that patience is a virtue (especially with ourself) and what we really control (our skills, that’s all!).

I would love to hear what you think.

Until next time. Thanks for reading!

Resources:

- Michael J. Mauboussin’s The Success Equation.