My Stanford professors used to say, “Good leaders know when to get off the dance floor and when to head to the balcony to get a better view”.

Most companies step onto the balcony this time of the year to build out their 3-5-year plans.

If they look at this complex market from first principles, they will be able to spot new opportunities.

India is large and rich

India is a nation of staggering scale with a 1.43 billion population.

An impressive 65% are under the age of 35.

With a projected GDP growth of 6.1% in 2023 (IMF), India has become the world’s fastest-growing economy.

Not just that, our GDP has expanded 9x since before liberalization1.

And our per capita GDP has grown 5.5x2.

But Indians are many and poor

The picture looks rosy in aggregate.

But not so rosy when we look at it from the perspective of every Indian – the average Indian’s income mirrors that of citizens in sub-Saharan Africa.

This Per Capita Income translates3 to Rs. 313,450/- per year.

What does this mean? This means that the average Indian does not have two coins to rub together. She cannot afford to consume as much as she would like to in one go. It’s not a lack of desire or that she is stingy – it’s simply the lack of spending muscle.

Let’s make this real.

Let’s see what this looks like in real life

I share Thayyal Nayagi’s example from the excellent book, Whole Numbers and Half Truths by Rukmini S.

Between Thayyal and her son, they bring home Rs.34,000 per month. That’s more than Rs.4 lakh a year- much higher than the average. But when we net-off obligations like loan interest payments, they have little to spend on life’s essentials – roti, kapda aur makaan (food, clothes, and house).

They pay off two loans – one taken by her late husband4 and the second for a bike her son needs to get to work.

They also contribute to a self-help group5 and are left with Rs.5,875 of spending money for each of them. It’s barely enough to make ends meet and does not leave room for any indulgences or impulse purchases.

Ironically, the income of Rs.4+lak puts them amongst the top 20% of richest Indians.

Whichever average Indian family we look at, the big picture remains the same – the average Indian simply does not have enough funds to consume huge quantities at one time.

This leads to consumer behaviors that are typical of this market but difficult to grasp by new business managers who over-commit and consistently underdeliver.

Aggressive projections and disappointed boards

Companies enthusiastically assume that a large population translates into a vast consuming base.

Just as even carelessly thrown seeds sprout on fertile soil, they naively assume that launching products is all it takes to succeed here. So they confidently commit ambitious targets to their boards and invariably fail to even scratch the surface.

I have experienced this first-hand. Not once, but twice.

Lipton Ice Tea and Nesplus Breakfast Cereals

About twelve years ago, I led the Lipton Ice Tea joint venture (between Unilever and PepsiCo). Our product was excellent. It was made with the best beverage technology available to us. This technology preserved the delicate taste of tea leaves, the product was natural and came in delicious lemon and lemon mint flavors.

Confident in the product and even more confident in the large opportunity a large population presented, there was no doubt in our minds that we would sell enough to break even by the third year (if not sooner).

We were in for a rude shock. Eight months into the launch, even after practically giving the product away through ‘buy two get one free’ promotions, we still did not manage to sell all of it.

Each annual plan was an exercise in pulling revenue projections out of thin air and constructing them out of hope. Chastised by the consumer, we toned down our ambitions. When we did not feel confident that we would break even over a 3-year horizon, we extended the period to 5 years, then 6, and so on.

Even today, the business is more or less the same size. The only difference is that instead of spreading itself thin across three different trade channels – QSR (quick service restaurants like Subway), modern trade, and general trade – the business is concentrated in QSRs.

The story repeated itself in 2019. The Nestle-General Mills partnership launched Nestle breakfast cereals. Again, everybody fell prey to the “we will launch and sales will follow” myth.

Many businesses continue to pursue the mirage of an instant coffee-like windfall, only to discover that India is more like the drip-drip of a slow but dependable percolator.

If this has depressed you, I promise it’s not all doom and gloom. Next time I will share the happy story of an overnight success.

In summary, we truly really fully understand the Indian market when we deaverage the numbers. We will do that in the next edition and see that India is not one, but four different markets.

Thanks for reading.

Sources

- $1.58 trillion in 1990 to $9.27 trillion in 2021. Source: World Bank, 2017 Constant prices ↩︎

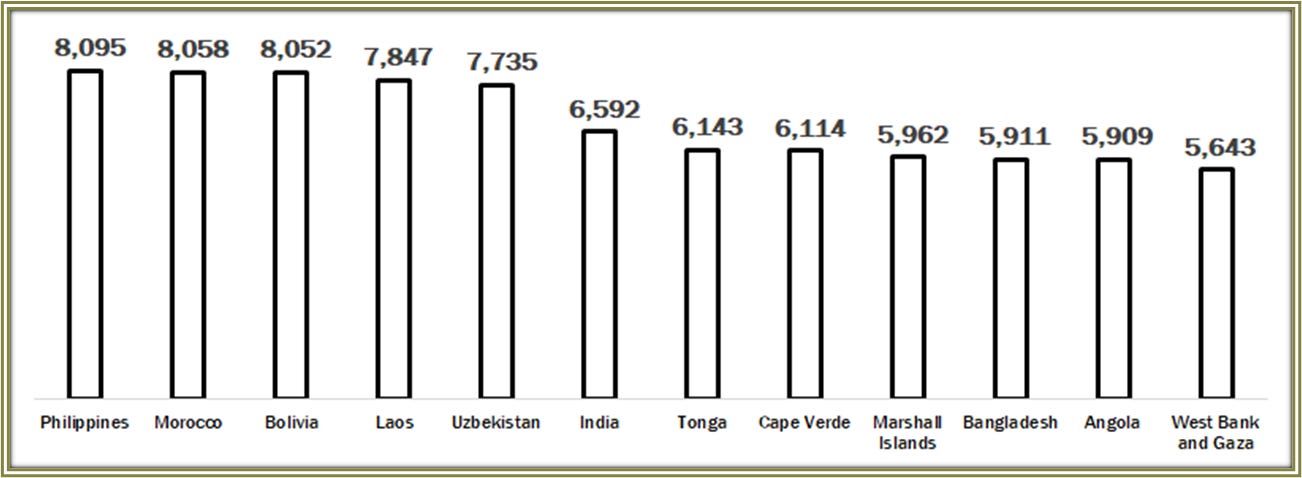

- $1,189 in 1990 to $6,592 in 2021. Source: World Bank, 2017 Constant prices ↩︎

- PPPs of the Indian Rupee per USD was 20.65 in 2017 and 15.55 in 2011 (which means that $1 and Rs.20.65 bought the same products and services. The exchange rate of Indian rupees to USD was 65.12 in 2017 and 46.67 in 2011. So the PLI was calculated as 47.55 in 2017 and 42.99 in 2011. ↩︎

- In the book, Rukmini shares the backstory. Thayyal’s husband was an alcoholic and unemployed. So he borrowed heavily to fund his lifestyle. After his death, the debt becomes Thayyaal’s responsibility. Each month, she can only afford to pay a part of the interest and has not been able to pay any part of the principal amount yet. ↩︎

- Self-help groups are micro-finance communities. Each member contributes funds which are then available for emergencies in the form of collateral-free loans. ↩︎