If the brand is a layer of meaning surrounding a product, then fragrance is its invisible salesperson. It’s commonly known in the fragrance industry that if you wash the left side of your scalp with a zero-fragrance shampoo and the right side with the same shampoo infused with a fragrance, you’ll feel the right side is cleaner, softer, and shinier.

Fragrance not only makes us feel good, but it also makes us believe that the product works.

Just because it’s invisible, don’t ignore it.

Today, I explore the psychology of why fragrances work the way they do.

- We smell in our brains, not our nose

- Fragrances Trigger Strong Involuntary Emotions

- Fragrances are autobiographical time-travel vehicles

- Autobiographical fragrances are called imprinting smells.

- Imprinting smells are context-dependent

- Our brain software updates itself

Next week, we will look at marketing examples and guidelines for using fragrances to turbocharge marketing mixes.

We smell in our brains, not our nose

Our sense of smell is probably the oldest of our senses. It was an essential survival tool that helped us sniff out good fruits from the rotten ones, and even in the dark, our cavemen and women ancestors could smell their way to safety – take a right towards the sweaty musk of a lion and left to the floral field of lilies.

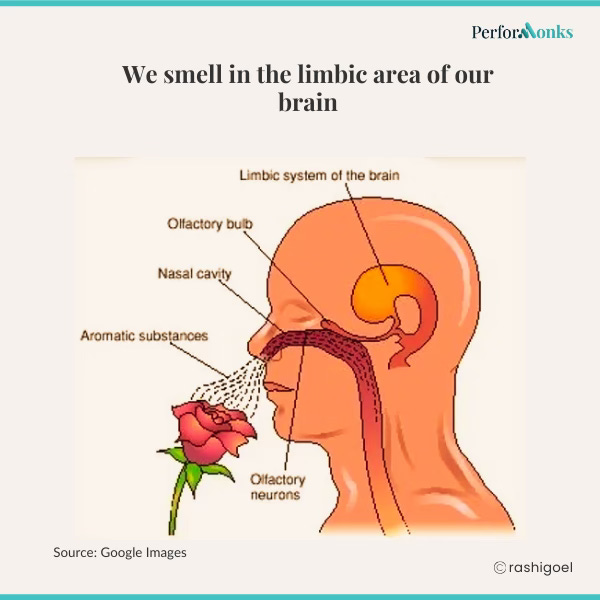

We may see a rose, but we smell it only when our brain tells us that it smells like a rose. The olfactory bulb in our nose picks up odours from the environment, converts them into electric signals, which our limbic brain runs through its database of more than 1,000 genetically coded ‘smelling cells’ and tells us what we are smelling.

In truth, we smell a rose even before we see it because out of all our sense organs, the olfactory bulb has the shortest and most direct connection to our limbic brain.

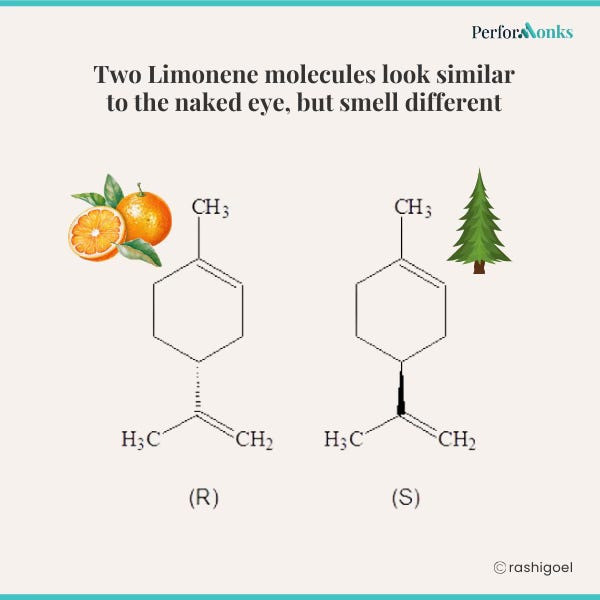

Fun fact: Two limonene molecules look so similar that a scientist’s eye can’t tell them apart. But a scientist’s nose can. One smells like oranges, and another like pine trees.

Fragrances Trigger Strong Involuntary Emotions

Our limbic brain (lizard brain) is the home to our memories (hippocampus) and emotions (amygdala). That’s why smells have the strongest power out of all other senses to evoke emotions and memories, often both together.

Ever wanted to go to the movies whenever you smell popcorn? Or thought of an ex-lover when you smelled their cologne on a stranger?

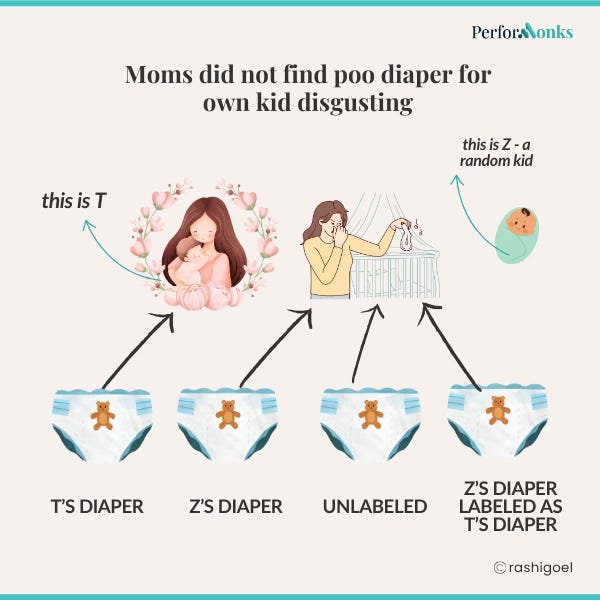

The sense of smell is such a powerful evolutionary tool that moms are wired to find their own babies’ poop less disgusting. [Source]

In a scientific test, mothers of 14-month-old infants compared the smell of dirty diapers from their child to that of an anonymous infant. They found their child’s diaper to be less stinky even when the labels tried to trick them:

- Both diapers were unlabeled

- Correctly labelled

- Incorrectly labelled (switching the labels)

Subscribed

Fragrances are autobiographical time-travel vehicles

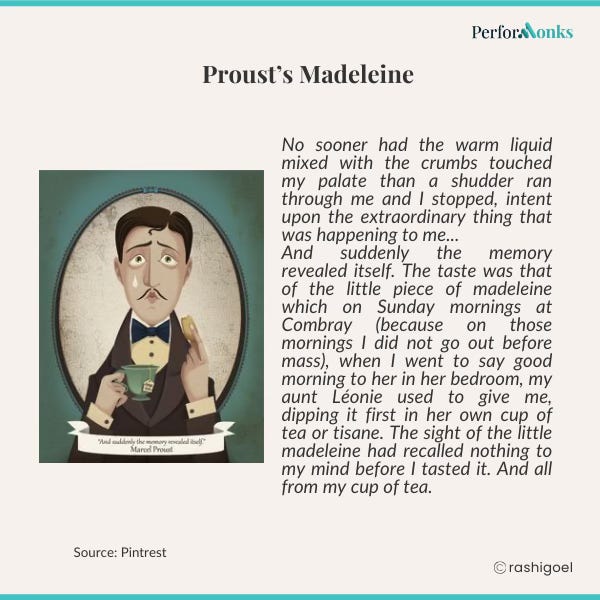

Any essay on fragrance is incomplete without the mention of Proust. Proust, one of France’s most influential authors of the 20th century, illustrates the power of fragrances to trigger memories in his book, À La Recherche du Temps Perdu or In Search of Lost Time.

He describes how the taste of a madeleine cookie dipped in tea brings back memories of his aunt. Here’s an excerpt:

Madeleine cookies dipped in tea was his imprinting smell – even decades later, they helped him remember what he had forgotten.

Autobiographical fragrances are called imprinting smells.

From the minute we are born, we are surrounded by smells. We start off with the smell of milk—sweet, sour, and soapy. Then, as we grow, we collect memories and experiences that have impacted us deeply, on-repeat experiences, even unhappy ones. Each of these has an associated smell—these get embedded into our limbic brain—and fragrance experts at Givaudan call these imprinting smells.

If fragrances can bring back positive memories, they can also trigger negative memories and emotions: Vermetten and Bremner proved that fragrances trigger negative memories for individuals diagnosed with PTSD. One Vietnam war veteran experienced guilt and helplessness whenever he smelt diesel—he time travelled back 30 years when, in the middle of burning vehicles, fire, and smoke, he was unable to save his fellow soldiers.

Smells changes across generations: Johnson’s baby powder might be an imprinting smell for folks in my generation because our mothers slathered us in it. Two generations later, today’s mothers may not use as much Johnson’s baby powder, so these babies will not have baby powder as an imprinting fragrance.

How do you know someone’s imprinting smell?

How do you know someone’s taste imprint? (The Morbid Approach)?

If we grow up with a certain toolbox of fragrances and experiences, does that mean we are locked in for the rest of our lives? Are we doomed to live ‘groundhog rose, sandalwood and jasmine’?

Not so.

Our brain software updates itself

The good news is that as we go through new experiences, our brain updates its software and broadens our fragrance likes and dislikes.

For instance, I don’t like musk melon fragrance. But I am a heavy user of moisturizers, and I keep trying all kinds of new ones. My brain might keep running into small strains of musk melon fragrance in different moisturizers. Over time, just like Chandragupta Maurya developed immunity to poison, I might just develop a liking for musk melon fragrance.

On the other hand, if I reject all products that even faintly smell of musk melon, my brain will never develop the plasticity to accept this fragrance.

As I finish writing this, I creep out into the night. It’s 11PM, and thanks to cloudy skies, I can’t see the stars. The door opens directly onto a lawn, wet grass, the chirping of crickets and the smell of clouds heavy with rain. I can hear the faint honking of cars in the distance. Like the squirrel, I shove my face into a pot of Jasmine, breathe in and tell myself, ‘This is what alive feels like.’

Thanks for reading. I’ll see you next week with a post about how brands can use fragrances to win a place in consumers’ minds.