When Ratan Tata first announced the dream of a ₹1 lakh car (USD 1,128 in today’s money), it was a visionary idea. He wanted Tata Nano to be “the people’s car,” a safer alternative to the scooter for a family of four.

The price tag of INR 1 lakh became their north star, and the engineering team even delivered this miracle!

Ironically, this very north star wrecked Nano’s success.

Tata Motors had overlooked that buying a car is not as cut and dry as trading in two wheels for four. Instead, the car we own signals how important we already are and that we are headed to important places. No one wanted to signal that they could not afford any better by buying the ‘world’s cheapest car’.

Tata Motors had made the fatal error of focusing on the wrong metric. They chased the internal metric of a ₹1 lakh price point and were blind to the leading metric – consumer preference.

We see this strategic blindness every day across thousands of corporate boardrooms – we lead with what lags and ignore what we should lead with. 99% of our meetings start with market share. Then we wade through reams of data on revenue growth, ROAS, ROI on consumer promotions, and acquisition costs. All 100% important. Yet, all 100% useless to track whether we are generating brand alpha.

When it comes to outgrowing the market, there’s only one lead indicator that matters.

Does your consumer prefer to buy your product (or service) over other options? And does she do this again and again? Over a long period of time?

Everything else is MBA gobbledygook.

So, what drives preference?

Three things.

We prefer brands –

- that we trust,

- that mean something to us, and

- that we notice because they are different from the others.

Like I said in the previous newsletter, when you have brand alpha with you, business results naturally follow.

Crafting brand alpha (read consumer preference) requires the imagination of Picasso and the precision engineering of NASA.

Oftentimes, it requires us to reframe not just what we offer, but also what consumers shouldwant.

Here are three examples of brands that squeezed out business growth by reframing both

1) Tata Tea: From commodity to purpose

We must balance the Tata failure at the start with a Tata success. This is one brand that got ‘purpose’ right.

For decades, Tata Tea offered taste, freshness, and aroma, hoping to grab attention and loyalty in a crowded tea market. This brand strategy was as effective as someone demanding they be crowned beauty queen simply because they have a nose, mouth and eyes.

The only saving grace was that because it was from the house of Tata, perhaps, it got the 15% share it had.

Take a look at this ‘freshly picked tea leaves’ (yawn) ad from the 1990s. Unforgettable only because it was so cringe.

Today, their share is 21% because they gave themselves a makeover.

Tata Tea became the tea that does not just wake you up, it awakens you. It awakens you to your civic responsibility as a citizen. Voting. Corruption. Women’s rights. When you buy Tata Tea, you buy into a civic movement.

The preference shift was real, and this led to the very real, but lag measure of financial growth.

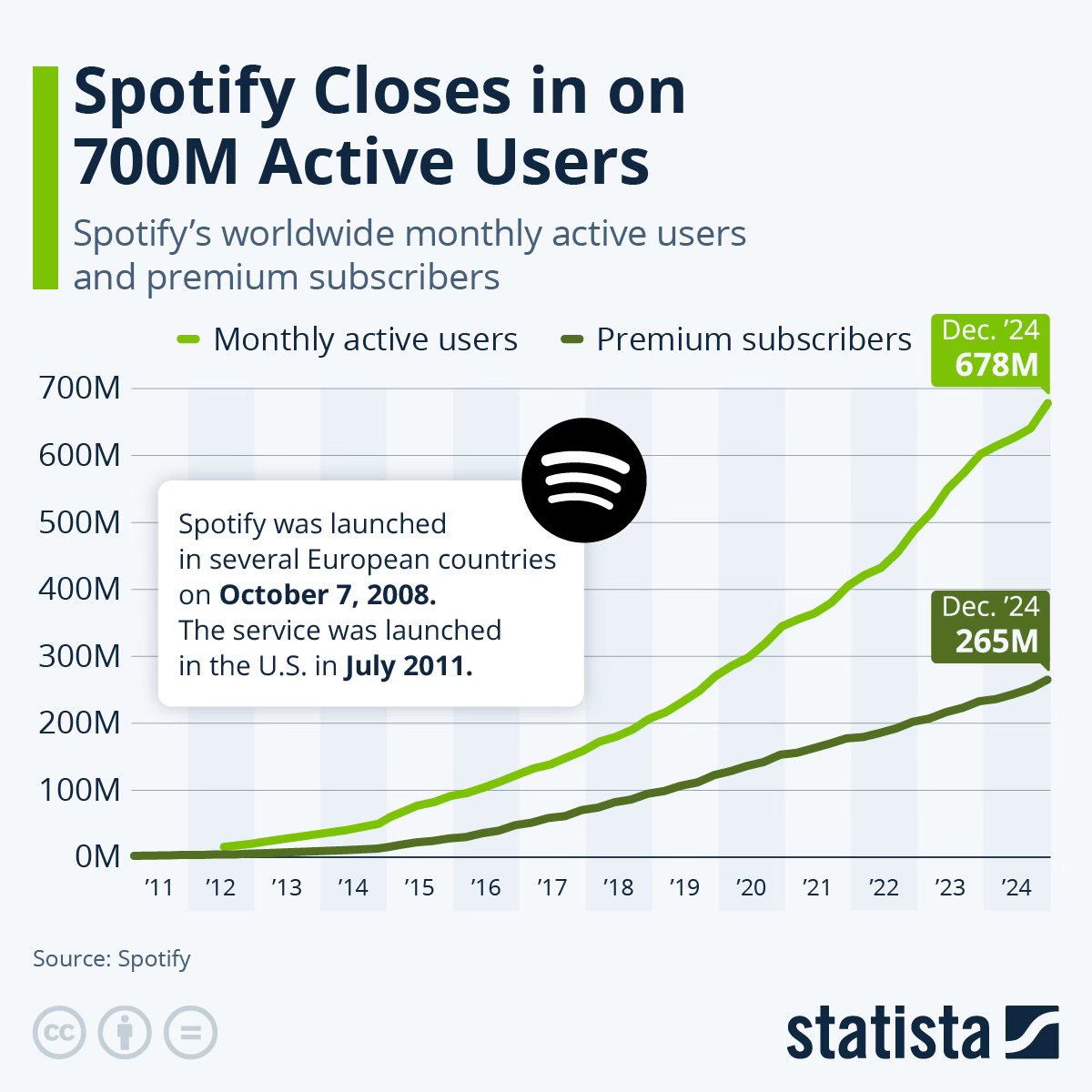

2) Spotify: From music aggregator to tastemaker

When streaming started, Apple iTunes dominated the market. All streaming platforms sell the same songs.

Spotify was just one more in the sea of sameness. Spotify knew it would drown unless it moved from distribution to curation. From the day their AI bots started curating personalised playlists for each user, Spotify was no longer a music storage cloud, but a “tastemaker.” Spotify became a musical genius that gently guided you to songs it knew you wanted to hear before you did.

Today, Spotify is the global music streaming platform, with ~30% market share, Amazon and Apple notwithstanding.

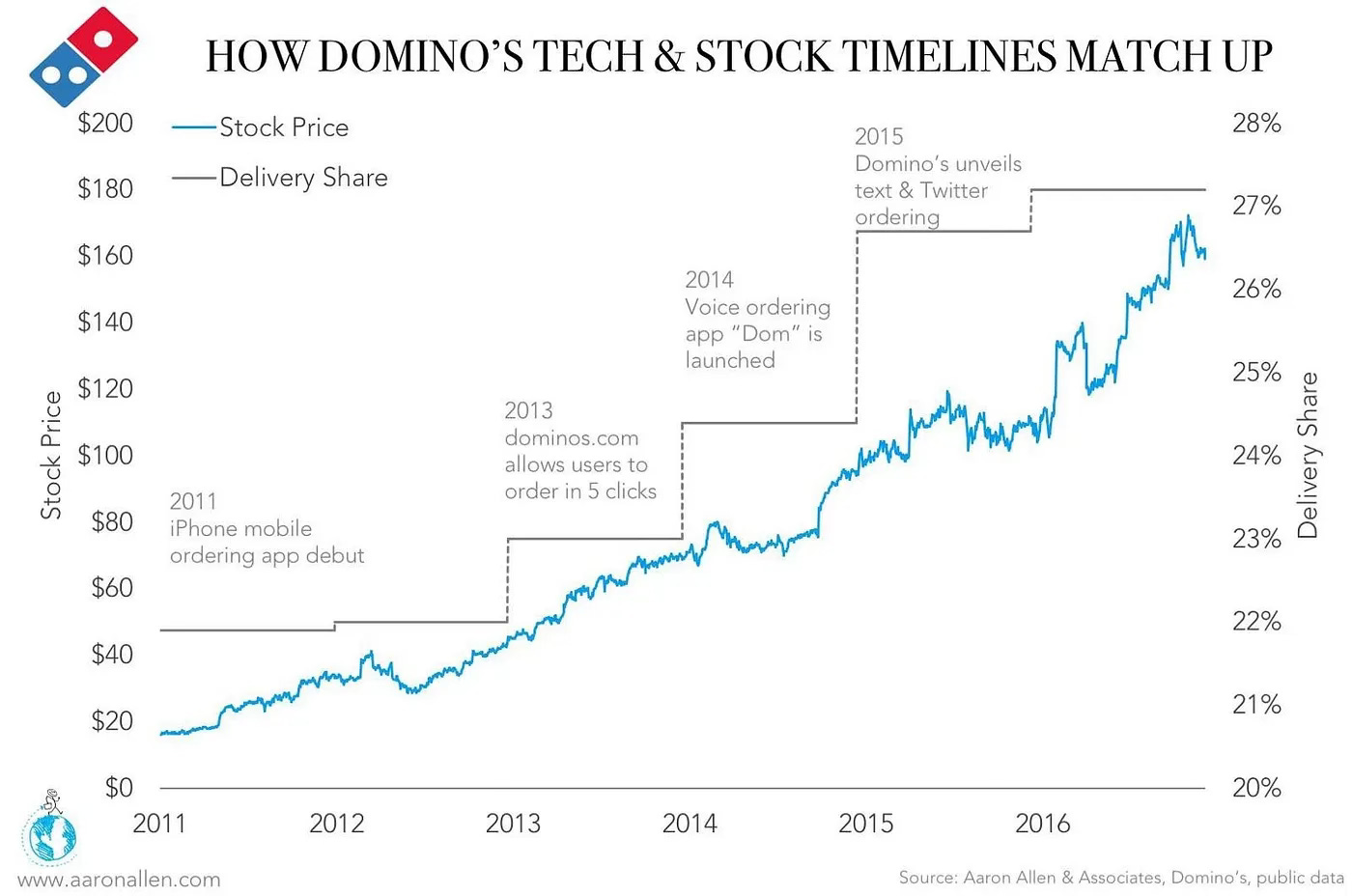

3) Domino’s: From pizza to 30-minute delivery

In 2009, Domino’s was pelted with poor reviews. Consumers hated their pizza.

Improving pizza recipes would have been the equivalent of chasing the INR 1 lakh price tag because consumers were comparing Domino’s to restaurant-quality, wood-fired Italian pizzas. This was not the right competition set. Domino’s was meant for when you were too lazy, too underdressed, and too comfortably snuggled in front of your TV.

So they invested in a technology and delivery infrastructure to reframe consumer preference from “restaurant quality pizza” to “hot, fresh pizza delivered faster than anyone else.”

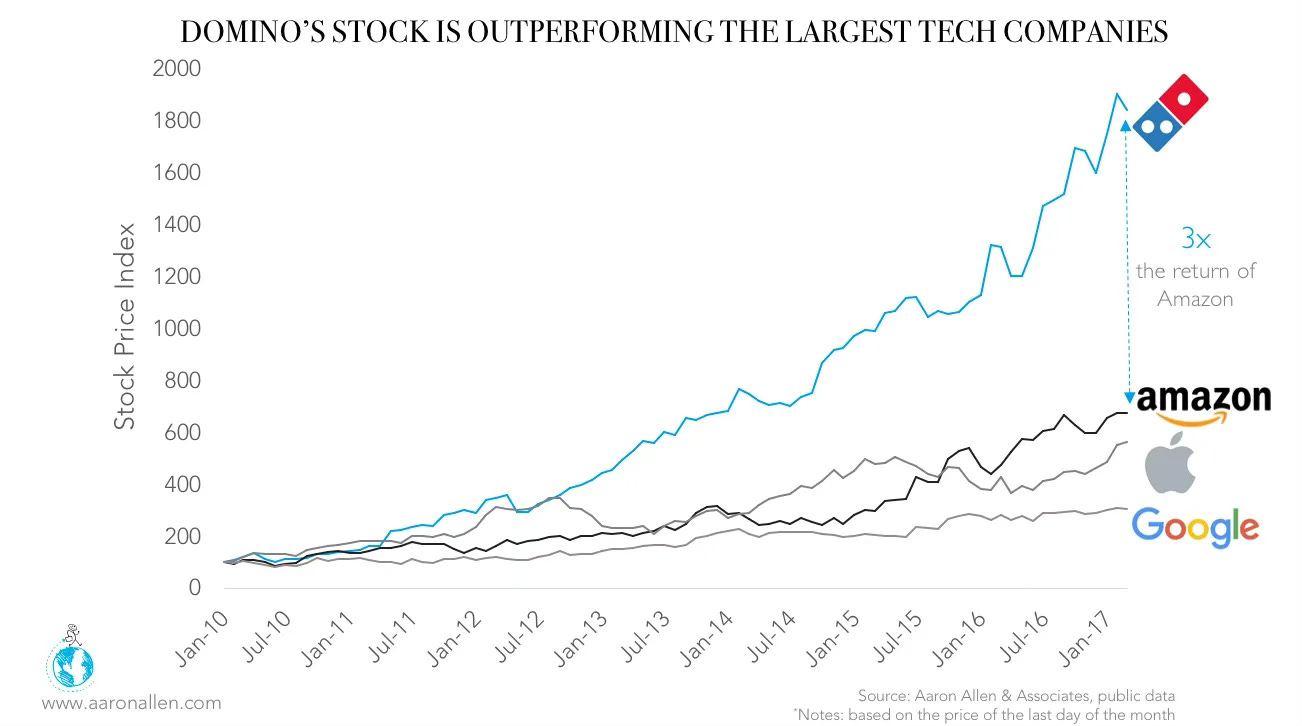

This chart proves beyond doubt that when we Picasso-NASA preference, business results follow. With each move to level up their delivery experience, their stock price soared.

Not just that, their stock price increased by 1000% from 2010-17, and even outperformed the tech darlings in those initial years.

What about the product? Is that not important?

It is. When you build the world’s first mousetrap. Your product is 10X better than the status quo, and people beat a path down to your shop.

But a new category becomes old very fast. Competitors enter. Product advantages disappear, and margins start thinning. All playbooks start converging.

In such situations, if you have a good product and get the nuts and bolts right, you may grow in line with the market. But when you add a layer of brand meaning on top of this, you get an “extra edge” that lets you charge more, win loyalty, attract better talent, and even survive downturns.

Simply put, products may give returns in line with the market. Brand meaning generates alpha growth.

Marketers are not bean counters

Forget valuation, LTV over CAC and number of reshares. That’s just accounting.

Instead, be honest with yourself. If you cannot answer, why did (or why did not) your consumers buy you over other alternatives, in a way that your grandmom will understand, you might be operating in a haze of strategic blindness.

More ways to connect

- Watch my Tedx talk

- Connect on LinkedIn

- read the Archives

- Subscribe to this Newsletter